Reducing dependence on imported natural gas will be a key strategic effort for European security over the next 50 years. Steadily declining production from dwindling fields in the UK, Norway and the Netherlands means Europe will need to import ever larger volumes of gas. This gap will widen over the coming years particularly in the European Union. This is because most industrialized countries are experiencing a growing gas supply gap caused by coal and nuclear plant retirements in parallel with increasing demand for natural gas from India, China, and Africa.

As the world makes a transition from fossil-based to zero-carbon energy, it is moving towards a balance of solar and wind power plus natural gas. The International Energy Agency (IEA) believes that by 2025, solar, wind, and hydroelectric generation will account for as much as coal and gas. In order to keep warming under the 2°C threshold agreed at the 2009 Copenhagen climate meeting however, greenhouse gas emissions in 2050 will need to be 40% to 70% lower than they were in 2010. These changes, along with accelerated renewable energy growth, transport electrification, energy-saving and efficiency, and carbon neutral infrastructure would make it possible to achieve 90% of required emission reductions but the remaining 10% will continue to emit carbon. Although most industry commentators expect coal use to eventually decrease rapidly, natural gas will play a substantial role in the global energy mix for some time.

Global Reserves and European Imports

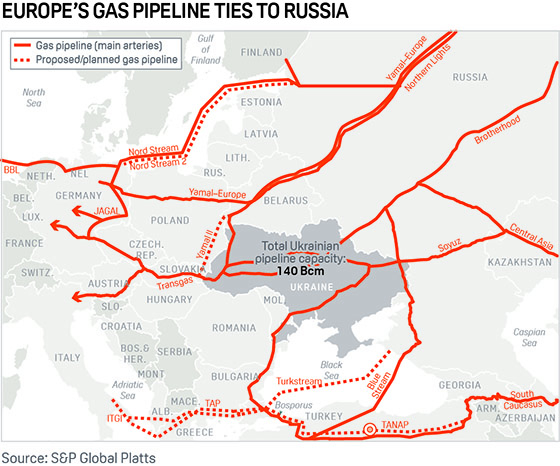

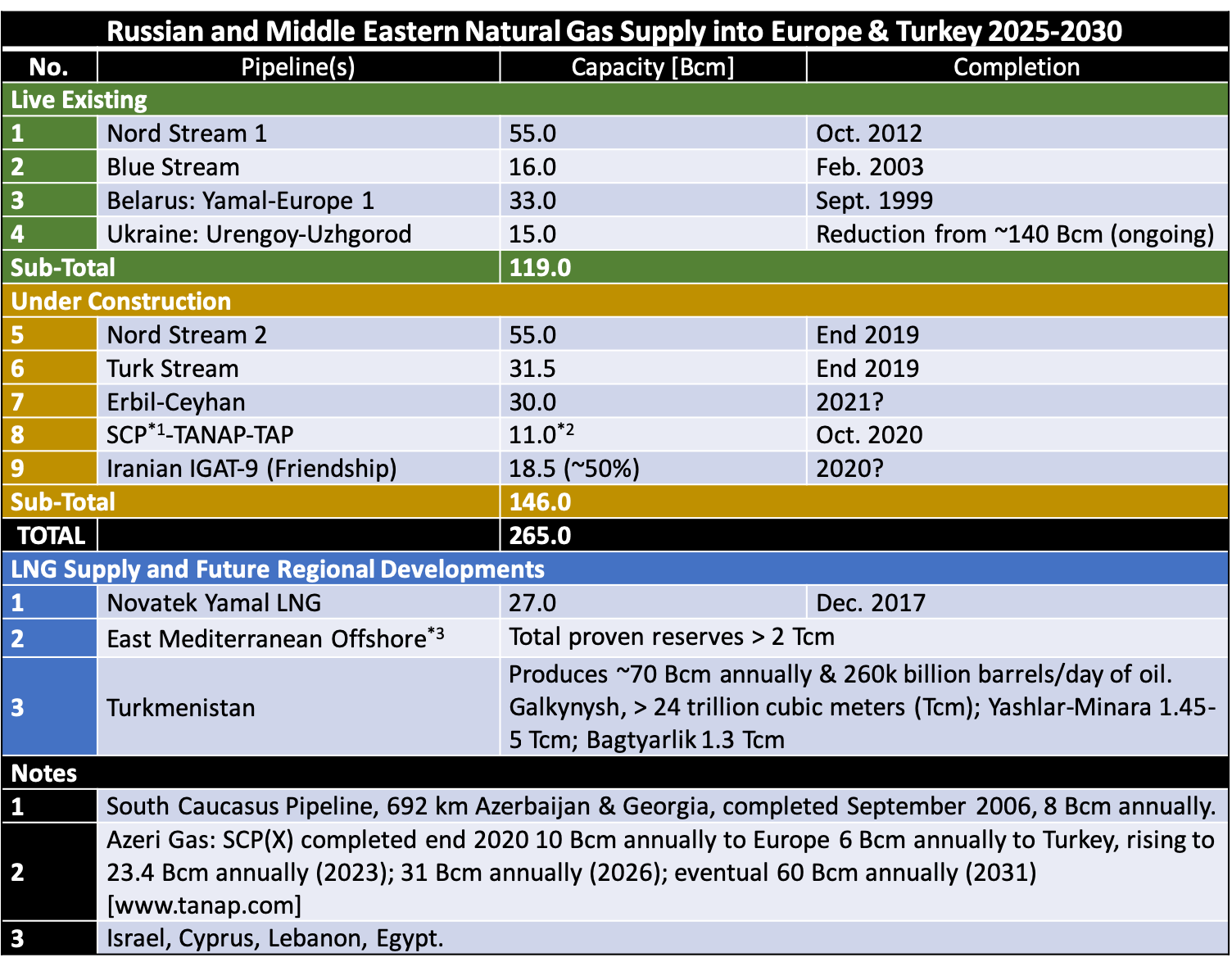

An overwhelming 83% of the world’s natural gas reserves are located in just 10 countries. Four of those countries – Russia, Iran, Qatar, and Turkmenistan – contain 58% of global reserves. The Russian economy in particular depends heavily on oil and gas, which provides ~40% of federal revenues and a tremendous incentive to use gas exports as a politically coercive foreign policy tool. Europe now imports about 43% of its natural gas through a Soviet era pipeline network crossing Belarus and Ukraine. The Blue Stream pipeline, installed under the Black Sea in 2003, allowed some diversification in Russian export capacity into Europe but by mid-2019 approximately 90% of European imports of Russian gas flowed via a combination of the Baltic Nord Stream 1 pipeline, completed at the end of 2012, and the Soviet era network that sometimes operated above its designed maximum flow capacity.

Collectively, these Russian operated/influenced pipelines and newly built LNG projects offer Moscow tremendous influence. In 2009, Russia used its Gazprom-owned pipelines to apply economic and political pressure on Europe and Ukraine. Although Europe weathered the crisis, Russia struck again in January 2015. This time, Norway compensated for the Nord Stream 1 export cut resulting in a USD $5.5 billion loss in Gazprom revenue and fines of $400 million. Europe was able to make a political point but Norwegian bailouts will not be feasible over the long term.

Politics, not geography, guides the future of Europe’s energy supply. According to Gazprom’s “optimization program”, most of the pipelines and associated infrastructure crossing Ukraine will be decommissioned. Gazprom shut down three compressor stations in 2018, with plans to eventually close 4,160 Km of pipeline and 62 additional compressors, leaving the Ukrainian network with little more than 10% of its original capacity. At the same time, the construction of Nord Stream 2 will permanently double Russia’s transmission capability outside Ukraine making Kiev highly vulnerable to Russian coercion. It is not difficult to see that Russia is bypassing Ukraine in favor of direct access to European and particularly German markets. In addition, pipelines across the Black Sea and those further south, including some under construction or planned, are likely to solidify Russian standing in Turkey and the Middle East.

Minding the Natural Gas Supply Gap

Russia’s strategy starves Ukraine and Slovakia of much needed transit fees and some degree of political independence. The strategy could also leave Europe more directly dependent on Russia to fill the European gas gap. With EU/Norwegian domestic production estimated to fall to 150 billion cubic meters (Bcm) annually by 2030 and consumption rates estimated at up to 510 Bcm annually – a 2010 figure – about 80% (360 Bcm annually) of EU imports could be Russian controlled or influenced by 2025.

These numbers are not favourable for Europe, which intends to meet some of the predicted increase in demand with Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) imports mostly from Qatar, Algeria and Nigeria but even this will not protect them from Russian influence. Russia has plans to capture 15%-20% of the global LNG market that would make it extremely challenging for costlier American LNG to counter Russia’s Siberian exports. Part of these plans depend on expanding the three train Arctic Yamal LNG to four LNG trains that can transport 29 Bcm annually. The $27 billion project is owned by Novatek (50.1%), China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) (20%), Total (20%), and China’s Silk Road Fund (9.9%), financed primarily by Chinese banks. The first shipment to UK via Yamal LNG was 170,000 cubic meters (equivalent to 0.1 Bcm) delivered by the LNG vessel Christophe de Margerie Arc 7 in December 2017.

Even importing gas from beyond Russia’s sphere of influence will be difficult. Importing the equivalent of Nord Stream 2 pipeline would require about 8 to 12 LNG vessel trips per week and competition is fierce. Though Qatar lifted a 2005 moratorium on further LNG development in April 2017, major announcements this year indicate the North Field Expansion (NFE) project will expand production from 105 to 170 Bcm annually by 2024. These developments included new jack-up drilling rigs, four new LNG trains, and a shipbuilding campaign to deliver 60 new LNG carriers and suggest most of the expanded production is destined for Southeast Asia. Future strategic supplies from developing offshore fields in the eastern Mediterranean may supply Europe, but Turkmenistani gas is likely to go east to markets in Pakistan, India, and China.

Geo-Strategic Imperative

Geo-Strategic Imperative

With LNG seemingly unable to meet Europe’s gas gap, nine infrastructure projects Russia is currently developing can be viewed as an investment in Moscow’s influence in the EU. It is quite possible these nine projects could eventually provide something close to ~290 Bcm annually in export capacity for supply into Europe, with roughly 50 Bcm annually from the IGAT-9 and Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) Pipelines delivered to the SCP-TANAP-TAP Southern Gas Corridor (see map). Based upon past instances, Russia could “weaponize” this near monopoly over natural gas and use it to apply political pressure but this time with greater effect.

There is therefore a geo-strategic imperative to substantially reduce European natural gas consumption. Improving the balance between gas, solar, and wind energy will have important geopolitical benefits including reduced fossil fuel use and improved human health and security. Acceleration of the development rate of renewable energy technology is essential. Adopting a faster rate of transportation electrification, and government support to reduce gas consumption can mitigate the effects of Russian pressure but it will not solve the problem completely. Governments must also accelerate developments in nuclear fusion, carbon capture and storage technology, and possibly clean zero emission shale gas extraction. Diversification of energy sources and the reduction of consumption is a win-win for Europe and the only way to fully mind the gap and escape the pressure of natural gas dependency.

Chri s Golightly is an Independent Consulting Engineer specializing in offshore renewable energy, based in Brussels. Prior to 2010 he worked in the Oil & Gas industry.

s Golightly is an Independent Consulting Engineer specializing in offshore renewable energy, based in Brussels. Prior to 2010 he worked in the Oil & Gas industry.

Geo-Strategic Imperative

Geo-Strategic Imperative

Dino Mora is an experienced Intelligence and Security Operations Specialist with a demonstrated history of working in the international affairs industry. His expertise includes Intelligence Analysis/Reporting, Counterintelligence, TESSOC threats, Tactical, operational and strategic Assessment/Planning, Counterinsurgency, Security Training & Team Leadership. He has extensive experience in NATO multinational operations and intelligence operations. Multilingual in Italian, English, and Spanish. He graduated from the Italian Military Academy.

Dino Mora is an experienced Intelligence and Security Operations Specialist with a demonstrated history of working in the international affairs industry. His expertise includes Intelligence Analysis/Reporting, Counterintelligence, TESSOC threats, Tactical, operational and strategic Assessment/Planning, Counterinsurgency, Security Training & Team Leadership. He has extensive experience in NATO multinational operations and intelligence operations. Multilingual in Italian, English, and Spanish. He graduated from the Italian Military Academy.

As the world’s leading geopolitical intelligence platform, Stratfor brings global events into valuable perspective, empowering businesses, governments and individuals to more confidently navigate their way through an increasingly complex international environment. Stratfor is an official partner of the Affiliate Network.

As the world’s leading geopolitical intelligence platform, Stratfor brings global events into valuable perspective, empowering businesses, governments and individuals to more confidently navigate their way through an increasingly complex international environment. Stratfor is an official partner of the Affiliate Network.