A low-intensity civil war has been raging in Libya since after its 2011 revolution. The situation escalated in 2014 after Islamists ignored the results of parliamentary elections and forced the parliament and internationally recognized government to seek refuge in eastern Libya. That same year Khalifa Haftar, Commander of the Libyan National Army (LNA) and loyal to the elected parliament, started a heavy-handed offensive to end an Islamist assassination campaign in Benghazi, the largest city in the east, where U.S. Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans were murdered two years before.

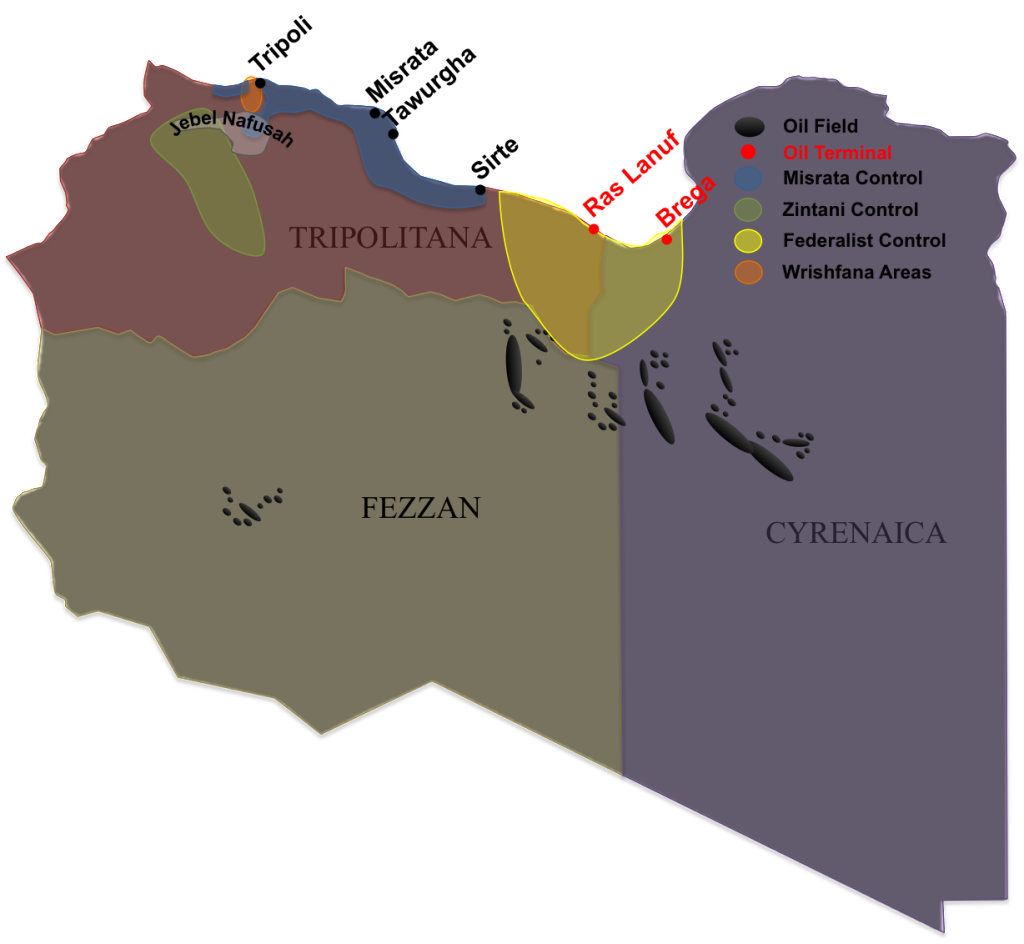

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) attempted to broker a deal, the Libya Political Agreement (LPA), focused on creating a new government. The LPA ultimately failed however because the negotiations were viewed as unrepresentative of actual power relationships on the ground. The internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA), formed by the LPA, relocated to Tripoli in March 2016 and has been under the de-facto control of Tripoli and Misrata militias ever since. Libyans outside of the Tripolitanian area reject the GNA and continue to complain about the perceived unfair distribution of resources and wealth as well as the criminal enrichment of the militias in the capital region.

An LNA offensive on the Tripoli in April last year torpedoed a UN initiative for a Libyan National Conference in Ghadames after several failed initiatives to revive the doomed LPA. In the eyes of many across the country, Heftar purposely tanked the initiative his supporters deemed unbearable. For the GNA and its allies, on the other hand, he simply seeks to establish a military dictatorship.

The Main Warring Factions

The conflict is primarily between the GNA and Marshal Haftar’s LNA. As the GNA has very limited capabilities, it is supported by Burkan Al-Ghadab (BaG), which is both the name given to the counteroffensive (and translates loosely to Volcano of Rage) against the LNA as well as the unofficial collective name for the anti-Haftar militias fighting for the government formed under the LPA. The BaG, strongly supported by Turkey and Qatar, is run by the Misrata militias, the largest single military block, and all of the major Tripoli militias. A larger number of radical Islamists including Al Qaeda (AQ) affiliates from the Tripolitania area fights among the ranks of the BaG, initially providing the backbone for several of its units. Several hundred Turkey-supported jihadists from Syria reinforced BaG early on in the battle for Tripoli. An alliance between the Misrata — Turkey’s closest allies in Libya and followers of Grand Mufti Sadeq Al Ghariani — and the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), that has maintained a strong influence on politics, security, and the economy in Tripolitania over the years, maintains a dominating control over the GNA and BaG.

The core of the LNA are army units supported by various loosely connected militias. Its key foreign backers (and weapon suppliers) are Egypt and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The LNA has a very wide definition of terrorism, considering moderate Islamists and AQ affiliates, as well as the Islamic State (IS) alike, as terrorists. This approach has merged the usually disunited Islamists into a firm anti-Heftar block.

The civil war in Libya is now a war of attrition with belligerents who have very different capabilities. LNA casualties are mounting as it is no match for the state-of-the-art equipped Turkish troops in Libya. These troops maintain combat drones, electronic warfare capacities, long-range precision artillery, warships, and, most importantly, impressive air defense capabilities. As of 20 May, after retaking the last remaining LNA base in western Tripolitania, Al Wattiya, the BaG offensive has gained momentum while the LNA tries to consolidate its positions in the south of Tripoli.

An International Playground

Libya is a geostrategically important country holding Africa’s largest oil reserves. Naturally, several other countries have important and vital strategic interests there. Security-related interests are mostly concerned with the various Islamist groups, ungoverned areas, and Libya’s porous borders which allow for smuggling and human trafficking. Additionally, there are value-related interests focused on promoting either democracy or political Islam. Finally, several countries are economically interested in Libya’s valuable hydrocarbon industry. Between Libya’s regional neighbors (Egypt, UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar) and concerned parties in Europe (namely Turkey, but also France, Italy, and Russia), all eyes are on the conflict between the LNA and GNA.

Turkey‘s troubled economy is in dire need of Libya as an important export destination and seeks a major share in reconstruction. The survival of the GNA and a leading role for Misrata are essential for Ankara’s economic interests. Turkey gives permanent residence to several prominent former LIFG leaders (a dormant former AQ affiliate), members of the Libyan MB, prominent former Benghazi and Derna Islamist fighters, and Libya’s Grand Mufti. Turkey uses their influence to pursue its interests in Libya. Qatar is also a major investor in Libya. Both Qatar and Turkey are providing weapons and military equipment for several of the pro-GNA militias, particularly those from Misrata. In fact, the Turkish military itself is the backbone of the war against the LNA.

Egypt, Libya’s neighbor, is closely watching the crisis across the border for any evidence of a terrorist safe haven developing so close to home. Libya is also an important labor market for almost one million Egyptians who cannot find work at home. Italy and France have significant strategic interests regarding Libya, but while, for Italy, the economy and migration are in the foreground, regional security and counter-terrorism are the French priority. For Moscow, the chaos in Libya is an opportunity to regain influence. Russia is most likely interested in getting a substantial share of the reconstruction business and influence over the hydrocarbon industry, particularly the gas market as well as establishing a “beachhead“ in North Africa. While there are no vital American national interests at stake in Libya, its instability is an increasing threat to US interests in the wider region.

Consequences of Developments on the Ground

After explosions significantly damaged the Misrata airbase on May 6, the LNA increased its efforts to achieve a breakthrough in Tripoli but is unable to make any progress. After the recent setback at Al Wattiya, and as Misrata airbase is fully operational again, the LNA will find it very difficult to maintain its remaining positions in Tripolitania without significant outside support from Egypt or the UAE.

Currently, there is no major BaG offensive operation east of Abu Grein – Wadi Zamzam, an area to the west of the oil-rich Sirte Basin. It is possible there is a tacit understanding between Turkey and Egypt that the BaG/Turkish offensive will stop short of Sirte and the central Al Jufra Oasis. However, keeping the significance of the hydrocarbon resources east of Sirte in mind, it is doubtful that such an agreement will hold. Furthermore, if the Cyrenaica separates from Libya as a consequence of the LNA defeat in Tripolitania, the Turkish-Libyan Maritime Agreement from November last year delineating their exclusive economic zones, an agreement of critical importance to Turkey, would become irrelevant.

If there is a military escalation between Ankara and Cairo over Libya, Egypt is in a much better position to provide direct logistic support without risk of interception. Fighter aircraft will be able to attack targets all over Libya directly from bases in western Egypt. Even ground forces could easily intervene if required, whereas Turkish transport aircraft, drones, or even fighters flying to Libya could be intercepted at ease.

If the LNA is defeated in Tripolitania, Turkey will become the dominant political and economic power in Tripolitania and Fezzan. This will have a huge negative impact on European strategic interests in Libya. It can be assumed that Turkey will become the favored economic partner of (western) Libya, strongly undermining the position of the various European stakeholders, in particular Italy and France. Turkey will also gain a more important position on the European gas market and will certainly be able to influence deliveries through the Green Stream pipeline that runs through Western Libya to Italy. Furthermore, Turkey will be able to control the pipeline’s central route towards Italy in addition to the eastern Mediterranean migration route to Europe. This will significantly increase Turkey’s ability to pressure the EU. Turkey will also probably continue to expand its political and economic influence towards Tunisia, Algeria, and the southern Sahara states. This includes support of political Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood and possibly some even more radical groups that will bring Turkey into conflict with vital French strategic interests.

A Civil or Regional War?

Libya’s civil war is home-made and its roots are domestic but it is not a typical proxy war. International support is key for both sides and will not end anytime soon. If one side loses its arms suppliers for whatever reason, the other would certainly prevail. No party trusts the other, efficient enforcement of the arms embargo is unrealistic, and Libya is simply too important. Regular demands for a “unified international position on Libya” or a “resolution between the two major parties” usually means unification of all efforts against the LNA. Keeping the deep rift within Libya and the strong interests from outside in mind, it is doubtful that such a “solution” has a chance to succeed.

Turkey’s President Erdogan is close to establishing facts on the ground by a combination of diplomatic and military action. The BaG is very likely to win the war as long as Turkish military capabilities in Libya are not neutralized and are able to sustain its efforts in light of mounting casualties and an eventual escalation in Syria. Egypt is hesitant to get fully involved in what could be a protracted and very costly conflict. Russia has limited capabilities and avoids even engaging the Turkish military in Syria directly and they are certainly hesitant to do so in Libya.

A political settlement is currently much less likely than a military decision, but with the potential upcoming defeat of the LNA at Turkey’s hand, it will not solve Libya’s problems. In fact, the situation could easily escalate and lead to a regional conflict leaving Europe and the United States to learn to live with the outcome.

Wolfgang Pusztai is a freelance security and policy analyst. He was the Austrian Defense Attaché to Libya from 2007 to 2012.