The Biden Administration’s strategic shift toward evolving threats in the Indo-Pacific signals an attempt to reaffirm the balance of power there in Washington’s favor. In a short trilateral statement issued from the White House on 15 September, President Biden — with Prime Ministers Scott Morrison of Australia and Boris Johnson of the United Kingdom — announced an enhanced security partnership they call AUKUS. Despite its brevity, the AUKUS declaration supports a profound broadening of pre-existing defense relationships in the region by means of technological, scientific, and industrial collaboration across fields such as artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, and cyber warfare. Though AUKUS was not explicitly aimed at the expansion of Chinese power, some clues about the agreement’s implementation cause most analysts — and certainly those in Beijing — to believe that it is. Regardless of how the messaging surrounding AUKUS is intended or received, it clearly has the potential to complicate Chinese designs in the region.

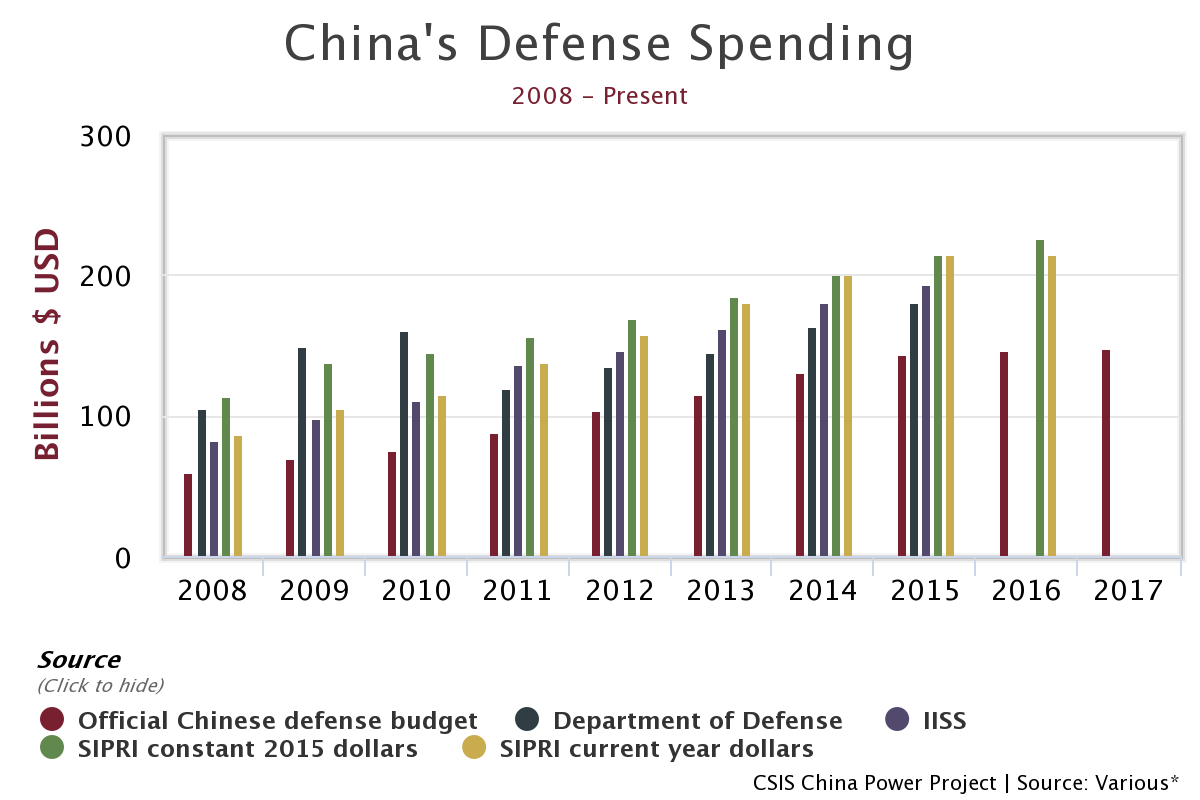

AUKUS sent a ripple that began in the South China Sea but surged heavily onto world capitals in East Asia and Europe. One heavily touted aspect of the pact is an agreement for the US and UK to provision the Royal Australian Navy with nuclear submarines; a capability that could radically curtail China’s economy in the event of a conflict. Though the submarine deal was presented as an economic move with military implications, Beijing dismissed any attempts at nuance as “extremely irresponsible” and stated the pact “seriously undermines regional peace and intensifies the arms race.” Still, considering the enormous expansion of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in recent years, including the development of multiple military outposts in the South China Sea and the expanding reach of the Belt and Road Initiative, some enhancement of regional maritime security seems necessary.

In initial remarks certifying AUKUS, President Biden made clear distinctions between nuclear-powered subs and those armed with nuclear missile systems. This distinction would allow for the use of weapons-grade uranium, provided Australia initiates and adheres to additional strengthening of safeguards on the production, use, and disposal of highly enriched uranium (HEU). Safeguards provided by the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) prevent nuclear warheads aboard the Australian submarine fleet and also restrict the use of naval HEU reactors. The move would make Australia the seventh country to field such assets and the very first non-nuclear weapons state to do so but also raises the concern that North Korea or Iran could obtain similar technology. Though it is not clear what specific contributions the US and UK will provide in terms of technology and HEU, this capability enables Australia to undertake a variety of operations far outside its territorial waters, putting pressure on the Chinese “nine-dash line” and complicating planning for Beijing.

Collateral Effect

Though differences exist between the Trump Administration policy and Biden’s current focus on pragmatism, it is evident that countering the developing threat of China remains at the top of the bipartisan list of priorities. The same is true in the UK where critics of Boris Johnson initially hesitated to label him as a China hawk. However, by capitalizing on the 2007 decision to buy two aircraft carriers, their impact within the Pacific theater is a powerful reminder of “Global Britain.” In this respect, the US has effectively hardened the UK’s line on China. In Australia, the heavy-handed influence of Chinese interference is felt more strongly through cyber-attacks and state agents acting under the cover of Chinese journalists. While foreign policy must weigh necessary contingencies against the country’s developing trade, economic, and investment relations with its autocratic neighbor, stepping into commitments with AUKUS presents much more than a defensive posture.

This expanding network remains most relevant in the 14-year-old Quad alliance consisting of Japan, Australia, India, and the US. As tensions continue to rise on all sides of China’s borders, the importance of the Quad is increasing tremendously. Taiwan regularly witnesses incursions of dozens upon dozens of military fly-overs, as do Japan’s nearby Senkaku Islands. Similarly, Indian and Chinese troops have repeatedly clashed in high-altitude tension in the Himalayas. Although critics are quick to write off these events as disparities common to the Indo-Pacific region, AUKUS offers more significant value given its intended depth. In addition to hardened physical boundaries, major strategies backed by the Quad and AUKUS have risen in importance over the past months as a counterforce to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. Build Back Better World, or B3W, announced in June at the G-7 summit in Cornwall, U.K., aims to counter Chinese influence through massive investment in infrastructure development of developing countries by 2035. The expansion is led by the principles of the Blue Dot Network (BDN) which sets standards for transparency and environmental impact in infrastructure projects in low and medium-income countries across the world. Among G-7 member states, there is talk of AUKUS broadening to align its activities with that of Japan, although such cohesion remains to be seen. Ultimately, this network will solidify spheres of influence to an extent not witnessed in decades.

Pending Reprisal

The most profound outrage regarding the AUKUS alliance erupted not in the Indo-Pacific, but in France. French President, Emmanuel Macron, was not notified of the pact before it was announced. France’s unsurprising response expressed betrayal by two NATO allies and aggrievement at the economic losses to its lucrative submarine deal with Australia. Though the French arguments seem justified, there was notable dissatisfaction with the submarine deal which was estimated to be nearly $70 billion over budget. Though observers debate the righteousness of French outrage, the opportunity it presents for China to drive a wedge between NATO allies is certainly more important. Faced with what European leaders are calling a “stab in the back,” Beijing’s recourse to diplomatic vindication is not unexpected. Indeed, Chinese diplomats contend that France’s vision of “strategic autonomy” is code for avoiding over-reliance on America. If China can effectively present AUKUS as an erosion of the NPT, it could provide further leverage in their efforts to divide the United States from its European allies far beyond Paris and in ways that are not directly connected to AUKUS.

President Biden’s apparent willingness to risk relations with France over AUKUS suggests a rearrangement of US security priorities back toward something that resembles the Obama Administration’s “pivot to Asia.” The extent to which this may justify the Elysee’s push for “strategic autonomy” will shape how well Washington can maintain a balance of power against China. For some, this balance is increasingly urgent. Michéle Flournoy conveys this sentiment more precisely in a Foreign Affairs essay in 2020: “It will take a concerted effort to rebuild the credibility of US deterrence in order to reduce the risk of a war neither side seeks.”

Travis Johnson is an active duty US Marine pursuing a MA degree in intelligence studies and is the associate editor for The Affiliate Network.

Travis Johnson is an active duty US Marine pursuing a MA degree in intelligence studies and is the associate editor for The Affiliate Network.

Lino Miani is a retired US Army Special Forces officer, author of The Sulu Arms Market, and CEO of Navisio Global LLC.

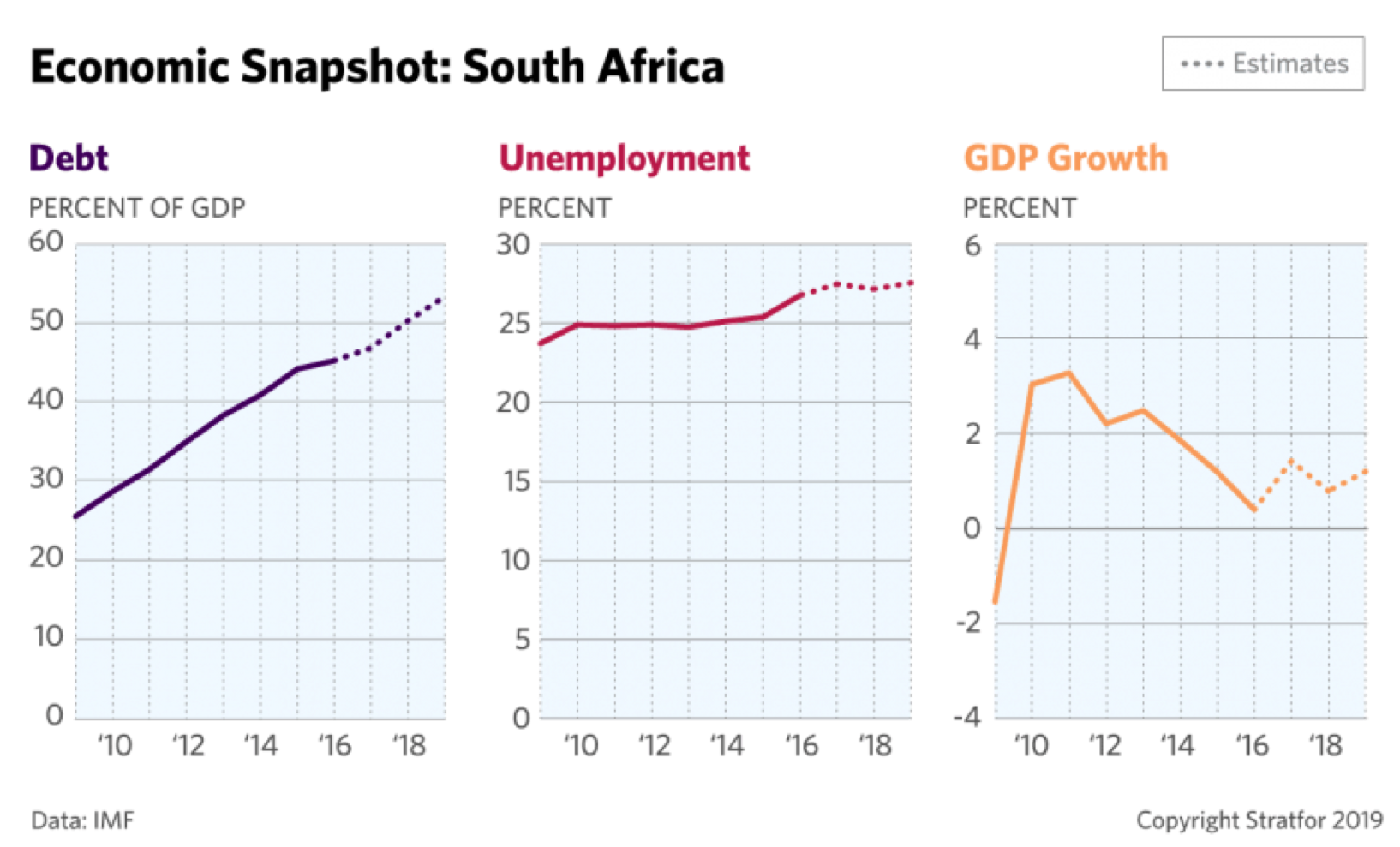

Despite the gravity of the situation, several of the country’s powerful unions have vowed to turn on Ramaphosa if he seeks to turn around Eskom by either privatizing the utility or laying redundant workers off. (According to the International Monetary Fund, Eskom’s workforce is bloated by a whopping 66 percent.) Should Ramaphosa opt not to alienate the powerful labor leaders who paved his path to the top of the ANC in 2017, he will have few policy options with which to deal with Eskom. In the end, one thing is certain: Failing to fix the company risks plunging South Africa’s economy into more crisis. As one Eskom board member recently warned, the current electrical grid cannot handle even a relatively minor uptick in economic activity without experiencing a system meltdown.

Despite the gravity of the situation, several of the country’s powerful unions have vowed to turn on Ramaphosa if he seeks to turn around Eskom by either privatizing the utility or laying redundant workers off. (According to the International Monetary Fund, Eskom’s workforce is bloated by a whopping 66 percent.) Should Ramaphosa opt not to alienate the powerful labor leaders who paved his path to the top of the ANC in 2017, he will have few policy options with which to deal with Eskom. In the end, one thing is certain: Failing to fix the company risks plunging South Africa’s economy into more crisis. As one Eskom board member recently warned, the current electrical grid cannot handle even a relatively minor uptick in economic activity without experiencing a system meltdown. Stephen Rakowski is a Sub-Saharan Africa Analyst at Stratfor

Stephen Rakowski is a Sub-Saharan Africa Analyst at Stratfor