In a speech marking the first year of his administration, President Donald Trump reemphasized a message he communicated many times during his campaign: that “open borders” promote the proliferation of drugs, weapons, and gangs. As distasteful as that message is, he might be right. Central America serves as a chokepoint for much of the drugs manufactured in the south. The region’s unique geography focuses the intense violence and vast sums of money required to control the drug trade and aims it squarely at markets in the United States. With many governments in the region still developing after the upheavals of the Cold War, Central America’s political geography is just as important as the physical. Corruption, poverty, and weak institutions provide the fertilizer for growth of the ultimate symptom of the regional disease: organized crime gangs known locally as “Maras.”

For Trump and his supporters, construction of a border wall seems like a common sense defense but the problem is more complex than bad people that want to cross the border. The Maras represent only one aspect of a complex regional problem that doesn’t lend itself to national solutions and certainly not to simple ones. So much so that President Trump’s politicization of border security reveals the weaknesses in his simplistic and unilateral solution: success requires the cooperation and assistance of regional partners. In some cases, these are countries the President recently referred to in derogatory terms. The subsequent cacophony of protests from around the world and the resignation of at least one US Ambassador (Ambassador John Feeley in Panama) indicate President Trump’s approach may enjoy limited success.

Highway to the USA

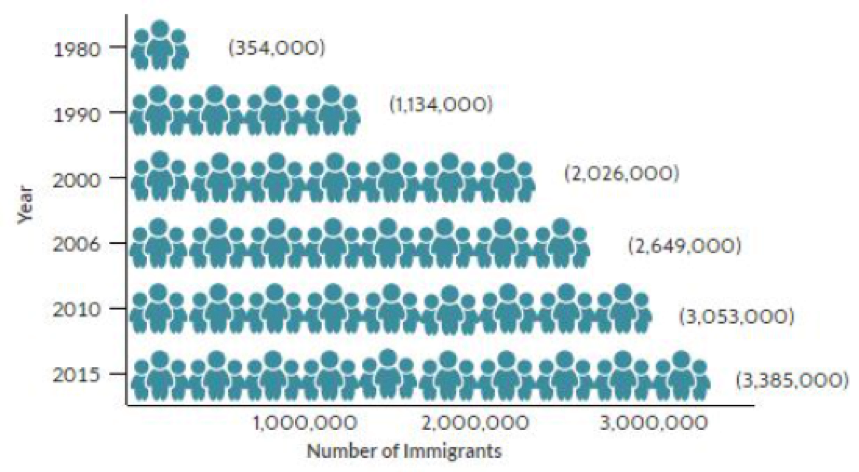

The Central American corridor has long been a direct path to the United States for gangs like the Maras. In the 1980s, they emerged in poor neighborhoods in Los Angeles, California. At that time, many Central American countries, particularly Guatemala and El Salvador, were suffering violent civil wars that displaced thousands of people to American cities. The traumatized and largely uneducated victims of those wars found shelter for their fragile new lives in poor expatriate communities there but it was not perfect; the perpetrators understood the utility of violence and organization and they lived among their victims in America.

When peace began to take hold in Central America in the 1990s, many of the combatant “guerilla” groups demobilized, expecting to inherit a place in peaceful societies that respect human rights. However, they faced an unbalanced political and economic environment with big social differences and poverty that inhibited structural change. As a result, former guerillas and gang members living in the United States found themselves unable to assimilate in their home countries. The problem was not a small one. With an estimated 100,000 gang members in the three small countries that make up the “Northern Triangle” alone, prison systems were beyond their capacity to serve as a deterrent. Today in El Salvador, the prisons are at 320% their capacity and are now simply a base of operations for the Maras.

|

NUMBER OF GANG MEMBERS |

||

| Country | Members | Source |

| Guatemala | 32,000 | UNODC (2011 statistics) |

| El Salvador | 60,000 | Ministry of Justice and Public Safety |

| Honduras | 36,000 | USAID |

With all the advantages of a peaceful sanctuary, the gangs began to strengthen. Groups like the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), Barrio 18, and the Batos Locos expanded their criminal networks and learned to survive as international outlaws. They established codes with tattoos, sign language, specific words, and proprietary clothing. They established a division of labor and territory and used violence to consolidate their control. By late 2016, the murder rate attributed to MS-13 in El Salvador approached 20 per day prompting more than one government to declare war against them.

Transnational Trouble

Though there is no internationally recognized definition of “transnational organized crime,” the United Nations does define “organized criminal groups” as:

“A group of three or more persons that was not randomly formed; existing for a period of time; acting in concert with the aim of committing at least one crime punishable by at least four years’ incarceration; in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit”.

The Maras certainly fit this definition, but existing tools of international law enforcement lack the muscle to address the sheer scale and intensity of gang violence leaving governments around the world struggling with whether to treat this as a criminal or terrorist problem. Recognizing this, and perhaps capitalizing on the Trump Administration’s own war on MS-13, Guatemala declared the Maras to be international terrorist organizations in January 2018, a move likely to win wide support from outside Central America. Salvadoran Maras for example, operate as far afield as Argentina, Canada, Mexico, Spain, and Italy where they actually established a capital in Milan, one of the most important cities in Europe and home to the largest concentration of Salvadorans outside the Americas. In 2016, the Buenos Aires Minister of Security, Cristian Ritondo, declared the presence of Maras there after dismantling a gang of drug traffickers connected to MS-13.

Labeling the Maras as terrorists seems a bit of a stretch given how they are organized and recruited. Social dynamics, not politics, fuel the Maras in Central America where some 45% of gang members come from a violent family background, 91% have illiterate parents, and 70% have experienced abuse or abandonment. Alcoholism and drug addiction are commonplace and for some, the gangs are their only real source of support, love, and loyalty. Maras are organized in neighborhood “clicas”, making it very hard for gang members to leave. Those that do wish to separate from the gangs face the twin stigmas of disloyalty and dishonor but also the structural realities of having to relocate. Those that manage to leave face a life full of harsh judgment, social isolation, and fear.

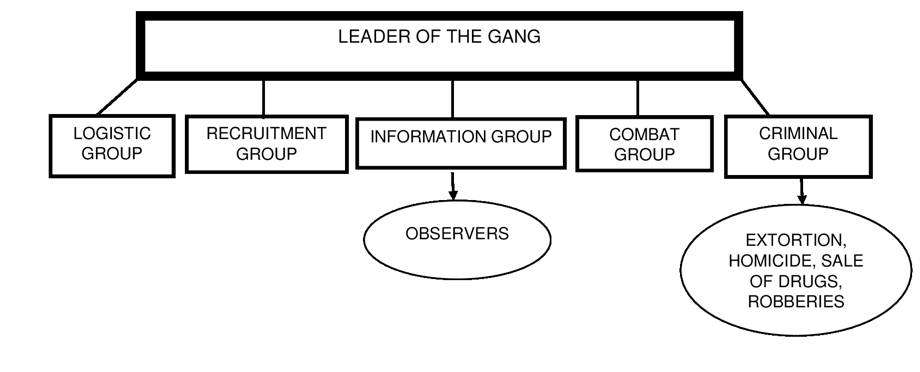

These young gang members are the foot soldiers of their organizations, executing most of their operations and falling into a paramilitary structure as depicted below. Their tactics include extortion of vulnerable individuals and small businesses by the threat of violence against them or their families. The young Maras also manage drug distribution on land, accounting for 59% of the overall trade.

STRUCTURE OF A “MARA” OR GANG

Whether the Maras are criminals or terrorists or a hybrid of the two, governments agree they present a transnational challenge. Fueled as they are by regional social issues, the Maras are therefore very difficult to control. Dealing with the threat posed by these groups requires governments to change their perspectives in terms of strategy, security, and power. Enforcement requires police with the intelligence capacity to gather information on Mara smuggling routes, weaponry, membership, specific mechanisms for moving money, and the type of people that protect them. Intelligence sharing mechanisms with neighboring governments are paramount in order to combat cross-border crimes. Additionally, corrupt politicians that secretly support the Maras for personal gain must also be prosecuted. Though walls like the one President Trump wants to build will keep some people out of the United States, it’s exactly the wrong approach for this complex problem. Success depends instead on the creation of international partnerships, information sharing, and reduction of social anxieties that drive members into a life of crime. Mr. Trump, tear down these walls.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and recently published this excellent piece on immigration issues.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and recently published this excellent piece on immigration issues.