A political earthquake struck Italy this summer as alliances shifted between bitter rivals in the country’s complicated multiparty system. Power plays, miscalculations and surprise deals made for juicy media headlines, but the most important lesson for the world may lie in the way one particular populist party allows technocrats to substitute technological farce for representative democracy. Though the crisis for government control made global headlines, the internal dynamics are somewhat difficult for outsiders to understand. In his 2015 book The Italians, author John Hopper observed that the turbulent surface of Italian politics may be by design. “[in Italian politics] issues remain arguable, and thus negotiable.” he wrote. “Imprecision is, on the whole, highly prized. Definition and categorization are, by contrast, suspect. For things to remain flexible, they need to be complicated or vague, and preferably both.”

In August, Matteo Salvini of the right-wing League Party created the most recent “turbulent surface” by making moves to bring down the coalition government in hopes he would then win a snap election. Despite his soaring popularity, an unlikely coalition led by the anti-establishment 5-Star Movement thwarted his attempt to gain control. 5-Star and its center-left former rival, the Democratic Party (PD), looked past their differences to freeze Salvini out completely. However temporary, sidelining Salvini and the League was a surprising outcome considering the rise of right-wing parties and leaders in Europe over the past few years. Many of these parties, including Salvini’s, have both overt or revealed links to Russia and its strongman president Vladimir Putin.

The “Non-Party” 5-Star Movement

Far from being a typical political party, the 5-Star Movement is a self-styled “anti-party” group that European journalist Darren Loucaides said “tapped deeply into one of the most powerful forces in Italian politics: disgust with Italian politics. Rather than offer an ideology or platform, Five Star offered a wholesale rebuke of the country’s entrenched, highly paid, careerist political class—left, right, and center.” A grassroots, populist movement, 5-Star emulated the profane style of its famous comedian co-founder, Bepe Grillo, calling some of its early events V-Days, a play on both the 2005 dystopian film “V for Vendetta” and a popular Italian vulgarity. Initially, the five stars in the group’s name referred to its policy priorities: sustainable transportation and development, public water, universal internet access, and environmentalism. Over the past 15 years however, that platform has expanded to include term limits, preventing those with criminal convictions from running for office, and now also a Universal Basic Income concept similar to the one making headlines in the 2020 US Presidential Race thanks to candidate Andrew Yang. Not so flatteringly, 5-Star has also been connected to anti-vaccination laws, the Brexit campaign, and American political operative Steve Bannon.

“When Grillo and Casaleggio founded the 5 Star Movement, few imagined they would reduce democratic freedom by doing so.”

Though Grillo was the public face of the movement for years, the man that truly orchestrated its rise to power was an unknown Italian entrepreneur and political activist named Gianroberto Casaleggio. Casaleggio used Grillo’s fame, straightforward internet blogs, and the Meetup.com platform to create a “grand techno-utopian project…an online voting and debate portal.” Casaleggio hoped to make the elected Italian Parliament obsolete, putting the power to legislate in the hands of the Italian people through their computers and smart devices. As Louciades wrote in Wired, as early as 2001 Casaleggio surmised technology would fundamentally change governments and politics, creating greater transparency and political accountability to the will of the people. He envisioned “interactive leaders” that deal directly with the masses, bypassing the media and its role as an interpreter. In Casaleggio’s view, a natural consequence of cutting out the media middleman would be the “imminent demise of journalism.” Society would be able to see politics as it truly is, not the “virtual reality” the media creates. He did not mince words: “Overcoming representative democracy” he said, “is therefore inevitable.”

Philosophers and Technocrats

Casaleggio named his direct democracy platform after the eighteenth century Enlightenment author and philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and set its launch date for April 13th, 2016. Unfortunately for Casaleggio, he died two days before its debut and would never know how Rousseau became central to the rise of the 5-Star Movement in Italian politics. Rousseau creates democracy without the use of intermediaries or the centuries-old political caste by allowing members to vote for candidates, create referendums on party decisions, propose and debate laws, and participate in fund-raising. As the internet and smart devices make the world ever more interconnected, the potential for these tools to facilitate direct democracy could mean drastic change for governance and politics. An idealist may believe that these systems, when integrated with blockchain or online-banking style security, could empower more voters and bring participation levels to new highs. A skeptic would counter that replacing representative democracy with internet-enabled direct democracy actually creates opportunities for coercion, cybercrime, and consolidation of political power in the hands of a few powerful technocrats.

Ironically, the 5-Star Movement has been roundly criticized for pioneering this technique though it directly contradicts their populist aims. When Grillo and Casaleggio founded the Movement, in part to cut the middlemen out of Italian politics, few imagined they would reduce democratic freedom by doing so. However, with power and information strictly controlled by a small group of technocrats at Milan-based Casaleggio Associates, 5-Star stands accused of silencing dissent. Italian author Silvia Mazzini compared Beppe Grillo to a populist dictator, ushering in new party members then threatening to ostracize or punish them if they do not support his ideas. Despite espousing a desire to empower the common citizen, Casaleggio Associates hand-picks candidates for the Rousseau elections without any transparency whatsoever. There are however, more obvious problems using Rousseau as a mechanism for direct democracy. In July 2019 there were only 100,000 active members on the platform, a tiny fraction of the 10.7 million Italians that voted for the 5-Star Movement in the 2018 general election. These are underwhelming numbers, even in a country where one out of four people still lack access to the internet.

The Future of Online Voting and Direct Democracy

Though access and participation are problematic, security is perhaps a bigger concern. Rousseau suffered several high profile cyber attacks in the run up to elections in 2017 and 2018. Hackers stole members’ information and even published phone numbers and passwords of party leaders in what was probably an attempt to intimidate voters and candidates. In response, the Italian data protection authority fined Casaleggio Associates for failing to fix several security flaws in their system. Italy is hardly the only nation experimenting with risky technology in the democratic process. The Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center released a report that, among other things, concluded “mobile and internet voting technologies are not presently secure enough for large-scale applications. Nevertheless, nations like Ukraine are “moving forward with integrating blockchain-based online voting into their national election systems in efforts to increase security and prevent voter fraud.”

Italy is the first large western republic to utilize an internet-based technological platform that purports to expand democracy on a national scale. As other republics around the world grapple with new wave populism featuring interactive leaders that use social media to bypass traditional filters, the integrity of democratic voting processes becomes a paramount concern. Italy’s ongoing experiment with Rousseau demonstrates that the security vulnerabilities of online platforms and limitations on participation, access, and transparency inherent in these technologies can make some voters more equal than others. The world will do well to look deeper and decide if this is truly an expansion of democracy or actually, as Gianroberto Casaleggio predicted, “democracy overcome.”

Jared Wilhelm is a Foreign Area Officer and former Naval Aviator who lives in Italy. He is a member of the Military Writer’s Guild, was named a 2014 Olmsted Scholar, and is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, and the U.S. Naval War College. His views are his own and do not represent the views or position of any other entity. He has previously published numerous articles on democracy around the world, including Some More Equal than Others.

Jared Wilhelm is a Foreign Area Officer and former Naval Aviator who lives in Italy. He is a member of the Military Writer’s Guild, was named a 2014 Olmsted Scholar, and is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, and the U.S. Naval War College. His views are his own and do not represent the views or position of any other entity. He has previously published numerous articles on democracy around the world, including Some More Equal than Others.

The operation is focused on the territory between the border towns of Tal Abyad in the west and Ras al-Ayn in the east. The Turkish spearheads are attempting to advance around the two towns, which are about 110 kilometers (68 miles) apart, and then drive down to the M4 highway about 30-35 kilometers away that runs on a parallel course to the border. Aside from Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn, both of which have a population of about 200,000, this territory is relatively sparsely populated and flat. The terrain and the dearth of major urban centers will significantly facilitate the Turkish advance, unlike the situation its military faced during its operations in Afrin and northern Aleppo.

The operation is focused on the territory between the border towns of Tal Abyad in the west and Ras al-Ayn in the east. The Turkish spearheads are attempting to advance around the two towns, which are about 110 kilometers (68 miles) apart, and then drive down to the M4 highway about 30-35 kilometers away that runs on a parallel course to the border. Aside from Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn, both of which have a population of about 200,000, this territory is relatively sparsely populated and flat. The terrain and the dearth of major urban centers will significantly facilitate the Turkish advance, unlike the situation its military faced during its operations in Afrin and northern Aleppo. As the world’s leading geopolitical intelligence platform, Stratfor brings global events into valuable perspective, empowering businesses, governments and individuals to more confidently navigate their way through an increasingly complex international environment. Stratfor is an official partner of the Affiliate Network.

As the world’s leading geopolitical intelligence platform, Stratfor brings global events into valuable perspective, empowering businesses, governments and individuals to more confidently navigate their way through an increasingly complex international environment. Stratfor is an official partner of the Affiliate Network.

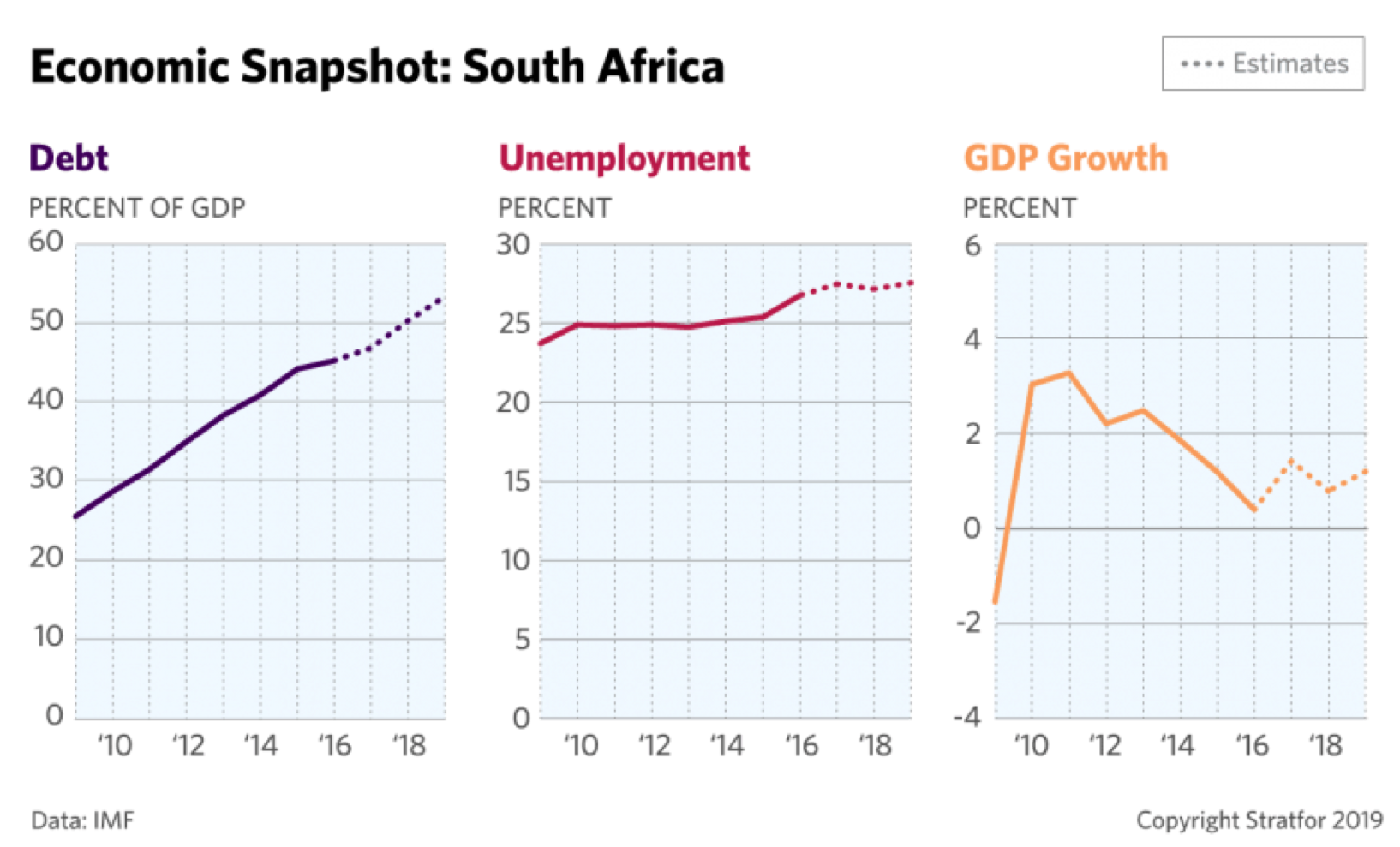

Despite the gravity of the situation, several of the country’s powerful unions have vowed to turn on Ramaphosa if he seeks to turn around Eskom by either privatizing the utility or laying redundant workers off. (According to the International Monetary Fund, Eskom’s workforce is bloated by a whopping 66 percent.) Should Ramaphosa opt not to alienate the powerful labor leaders who paved his path to the top of the ANC in 2017, he will have few policy options with which to deal with Eskom. In the end, one thing is certain: Failing to fix the company risks plunging South Africa’s economy into more crisis. As one Eskom board member recently warned, the current electrical grid cannot handle even a relatively minor uptick in economic activity without experiencing a system meltdown.

Despite the gravity of the situation, several of the country’s powerful unions have vowed to turn on Ramaphosa if he seeks to turn around Eskom by either privatizing the utility or laying redundant workers off. (According to the International Monetary Fund, Eskom’s workforce is bloated by a whopping 66 percent.) Should Ramaphosa opt not to alienate the powerful labor leaders who paved his path to the top of the ANC in 2017, he will have few policy options with which to deal with Eskom. In the end, one thing is certain: Failing to fix the company risks plunging South Africa’s economy into more crisis. As one Eskom board member recently warned, the current electrical grid cannot handle even a relatively minor uptick in economic activity without experiencing a system meltdown. Stephen Rakowski is a Sub-Saharan Africa Analyst at Stratfor

Stephen Rakowski is a Sub-Saharan Africa Analyst at Stratfor