Nearly 30 years since the invention of the world wide web, we have become accustomed to having high-speed, relevant content at our fingertips virtually everywhere we go. The availability of rapidly searchable information is now so important that the service economy globally is completely dependent upon the internet. Increasingly, automation and machine learning have made it possible to integrate the industrial economy as well. Public utilities, industrial and commercial supply chains, emergency response capability, transportation, and public health are all monitored and controlled via the web. Entire economies, governance, and even military power is now largely determined by availability of information…and it all rides on the thinnest of fibers.

If there is a physical structure to the internet, it is the thousands of miles of fiber optic cable that wrap around the planet. These tiny filaments are bundled into cables that carry trillions of terabits of data over mountains and under oceans at the speed of light. The amount of data exchanged daily between machines, sensors, and humans is increasing exponentially and includes everything from cat videos to military targeting data. For that reason, control of the internet, and the cables that carry it, has become a strategic concern for governments and industry alike.

The Thinnest of Threads

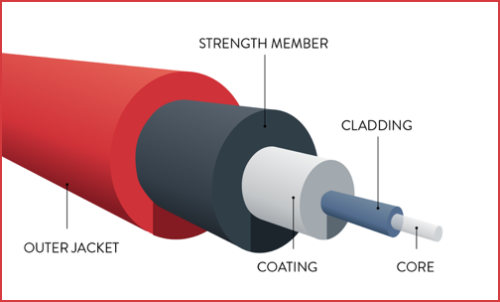

The cables that carry the web are simple in concept but complex in reality. Data, in the form of light, passes through tiny transparent fiber optic cables. These fibers, fractions of millimeters in diameter and made of glass, are unsuitable for use in the environment without reinforcement. With some variation, their structure resembles the diagram below with different layers designed to provide functionality and to protect the core from the elements and from breakage by stretching, creasing, or crushing. Adequately protected, the fiber assemblies are bundled into larger cables and laid across the ocean floor by specially equipped vessels.

There is nothing simple however about the function of fiber optic cables. The simultaneous transmission and reception of vast amounts of data on either end of the cable is a complex operation. Distributing that data across all the various fibers must be done with enough redundancy so that information is not impeded by tiny breakages or blockages along the thousands of miles of cable. However, transmitting all data on all fibers all the time is inefficient and instead must be done so that data can reliably reach specific destinations without wasting bandwidth. Balancing this distribution at the speed of light and monitoring the health of the cable along its entire length requires sophisticated servers and feedback mechanisms.

Despite careful management and protective measures, the cables are still vulnerable in a number of ways. Materials degrade over time, making the cables lose strength and possibly eroding their efficiency. They can be broken or damaged by fishing or survey gear, punctured by wildlife, or severed by landslides and earthquakes. On 26 December 2006, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Taiwan, severing eight cables in 18 places. The event severely disrupted internet connectivity in most of Asia for several weeks. Despite subsequent improvements to the strength, diversity, and resiliency of the network, it is still vulnerable to seismic activity and of course, there is no combination that is safe from intentional tampering.

Internet Bottleneck

Herein lies the strategic challenge and opportunity presented by undersea cables. All but one of the multitude of cables servicing Southeast Asia and the southern and western parts of the Indian Subcontinent pass first through the South China Sea. Not only is this an arena of intense strategic competition, but the sea itself is uniformly shallow making the cables relatively easy to access. While any reasonably capable state actor could cut these cables – certainly all those with claims in the South China Sea possess this capability – a more valuable, but more difficult, endeavor is to steal the information flowing through them. Though this is notoriously difficult with fiber optics, it is not impossible.

The techniques for tapping fiber-optic lines are a tightly guarded secret but the principle is an old one. Put a sensor on the line, record all the information that flows past it, and analyze it later. Naturally the lines are more vulnerable at retransmission stations called “regeneration points” and at “landing stations” where the cables emerge from the sea. Still, preventing such theft is not easy. Sensing technologies do exist to detect such tampering but it is not clear how effective they are or how dependent on interpretation. Even if tampering could be reliably detected, it cannot be prevented and it will never be possible to determine what information was stolen and what was not.

Strategic Geography

In historical conflicts, adversaries sought to deny each other access to critical resources or domains of competition such as the seas. In the event of a future conflict in the Indo Pacific region, it may not be possible for an adversary to deny Australia and Southeast Asia access to the world’s oceans, but it is indeed possible to limit their access to the lifeblood of the world economy. U.S. and Australian strategic planners take this problem seriously. They recognize for example there are no complete solutions to the threat posed by Chinese access to the South China Sea and the cables that lie underneath it. One partial solution is as simple as it is ancient. By laying a new cable from the United States to Australia, Indonesia, and Singapore, on a route that passes south of New Guinea, planners can protect the line by putting a tremendous amount of physical distance and defensible terrain between it and the adversary.

The route, which has obvious geographical advantages, also says something about the future of US-Australian-Indonesian relations vis-à-vis China. Interestingly but not surprisingly, the project is being implemented as a cooperative venture between private industry, the respective militaries, and in the case of the United States, as an economic development project funded by the Development Finance Corporation (DFC). The fusion of development with economics and security is not a new concept and is in fact a feature of imperial behavior throughout history. In the 19th Century the fuel that defined power in the Pacific was agriculture and coaling stations. In the 20th it was oil. In the 21st Century, it is — in part — the strategic role of information and the infrastructure that carries it.

Lino Miani is a retired US Army Special Forces officer, author of The Sulu Arms Market, and CEO of Navisio Global LLC.

Dino Mora is an experienced Intelligence and Security Operations Specialist with a demonstrated history of working in the international affairs industry. His expertise includes Intelligence Analysis/Reporting, Counterintelligence, TESSOC threats, Tactical, operational and strategic Assessment/Planning, Counterinsurgency, Security Training & Team Leadership. He has extensive experience in NATO multinational operations and intelligence operations. Multilingual in Italian, English, and Spanish. He graduated from the Italian Military Academy.

Dino Mora is an experienced Intelligence and Security Operations Specialist with a demonstrated history of working in the international affairs industry. His expertise includes Intelligence Analysis/Reporting, Counterintelligence, TESSOC threats, Tactical, operational and strategic Assessment/Planning, Counterinsurgency, Security Training & Team Leadership. He has extensive experience in NATO multinational operations and intelligence operations. Multilingual in Italian, English, and Spanish. He graduated from the Italian Military Academy.