One way or another, the biggest story of 2017 has been the Trump Presidency. Though we at the Affiliate Network have avoided commenting on American politics, it’s worth recalling that at this time last year, news outlets across the political spectrum were breathing a big sigh of relief as 2016, “the worst year ever” came to an ignominious end. At the time, the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) raged in the Middle East, Russian aggression dominated Eastern Europe, and China was staring down the world in the South China Sea. The United States and Britain seemed to shirk the traditional liberal world, gravitating towards isolationism and xenophobia and a number of other things were causing us stress. The New York Times was succinct: “Syria, Zika, Haiti, Orlando, Nice, Charlotte, Brussels, Bowie, Prince, Ali, Cohen…” Cohen? We’re not sure who that is but Carrie Fisher was a big loss right before Christmas.

Despite everyone else’s pessimism however, our Affiliates were looking forward to the challenges and opportunities of 2017. So, how did it end up? ISIL is on the run, global economies are steadily growing, and no matter how you feel about President Trump, 2017 did not end up as the “worst, worst year ever.” At the advent of 2018, we at the Affiliate Network would like to take the opportunity to look back and reflect on a year of detailed analysis of some of the world’s most important issues.

Mundo Latino (Latin World)

Latin America was one of our most-covered regions, and we are lucky to have a number of new Affiliates uniquely qualified to report on one of the world’s fastest growing regions. In Bolivarian Devolution: The Venezuela Crisis, Patrick Parrish and Kirby Sanford analyzed the precursors to the economic crisis and the social unrest that befell the oil-rich nation. While the crisis in Venezuela dominated headlines throughout the year, it was far from the only news coming out of the region. In Paraguay: Voting Away Freedom, Kirby Sanford explained how a strong leader and weak institutions led to a constitutional crisis that proved political instability is not an isolated event on the South American continent.

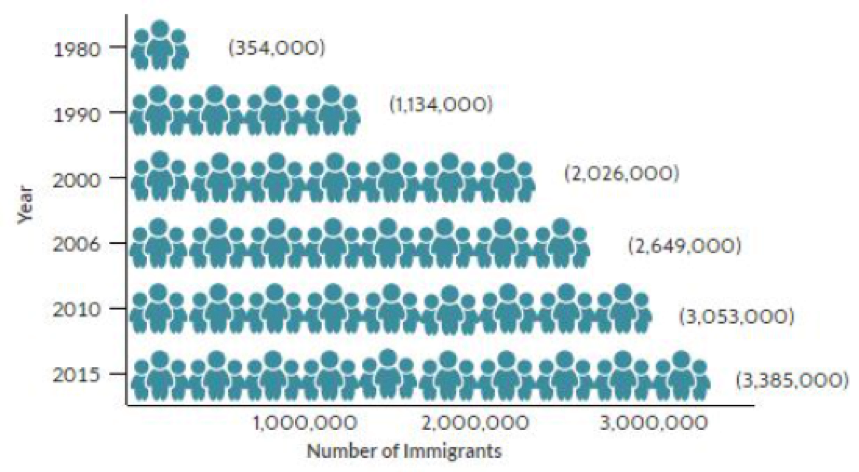

Naturally, authoritarian rulers are not the only sources of tensions in the Americas, some crises there are rooted in socioeconomic issues. In A Tale of Two Cities: Development in Latin America, Patrick Parrish examines growth and development in a region rife with inequality, a phenomenon that will likely be a future source of civil unrest there. As a result of this inequality, Latin America and the United States share the burden of a historically significant period of migration. In Feeding the Beast: Guatemalan Migration, Ligia Lee gives an insider’s assessment of the problem and suggests that addressing regional issues is the only way to stem the tide of migrants moving towards the United States.

Complex Emergency

While thankfully the issues in Latin America this year had mostly socioeconomic and political causes, in other regions, military conflicts were the primary drivers of change. Though the battle against ISIL is far from won, Iraq’s leadership declared a short-term victory in December by affirming ISIL no longer occupies significant territory in the worn-torn country. Meanwhile, Russia still occupies the eastern reaches of Ukraine where heavy fighting continues despite the fact that the conflict has largely fallen out of headlines. In Arming Ukraine: The Debate, Heather Regnault examines options available to world leaders to counter Russian aggression, and asserts that US strategic leadership is required to discourage additional Russian moves in the region. Similarly, Dr. Chris Golightly argues Russia’s boldness in the Middle East may be part of a larger plan to manipulate hydrocarbon markets in order to re-shape the geopolitical landscape in its favor. In Green is the New Black: Making a Gas Cartel, he examines Russia’s ambitions in the Middle East and adjacent Black Sea through the lens of geopolitical ambitions based on pipeline deals.

Worst in Asia

Asia was no stranger to political drama in 2017. In China, Xi Jinping consolidated power in the Communist Party and looks to continue guiding the nation’s rise to prominence. In Chengdu: Canary in the Coal Mine, Navisio Global’s own Lino Miani explains that Chinese economic growth is not sustainable in the face of an increasingly affluent and demanding middle class. Xi was not the only Asian leader making waves this year. In North Korea, Kim Jong Un also took steps to secure his position albeit through less conventional measures. In LOL: The Art of Assassination, Lino lends his unique insight to the details surrounding the brazen assassination of Kim’s older brother. The complex operation employed unwitting agents and the use of a deadly chemical weapon in the middle of a busy Malaysian airport. While the assassination answered the question of what lengths Kim will go to in order to secure his power as leader, it also raised fears of what he may be capable of doing with his growing nuclear arsenal.

Tech Monster

Technology and innovation emerged as an increasingly pertinent theme in global security in 2017. In Future Vision: Europe’s Image Problem, Johnathon Ricker explains how the end of the ISAF mission in Afghanistan left Europe without a crucial security tool: accurate and reliable satellite imagery. This reliance on technology for security isn’t just limited to imagery. In Industrialization’s Monster: Yes We Can, Dr. Jill Russel examines the global quest for innovation in technology through the reflective lens of the industrial revolution. She questions whether the technological and cyber revolution we have created will eventually develop the power to defeat us. Her analysis reminds us that when it comes to managing global security challenges we must also mind the tools and technology that power our economies.

The Affiliate Network would like to wish everyone a happy and healthy holiday. We assure you that the intelligence of our affiliates is anything but artificial, so be sure to check in with us throughout 2018 to maintain a high level of situational awareness on global security issues as they emerge. To our readers and followers on social media: a sincere “thank you” for all of your likes, shares and comments. The Affiliate Network team hopes that the coming year will be rich with constructive policy discussion at the family dinner table.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the views of any government or private institution.

Major Patrick “TISL” Parrish is the Blogmaster and editor for the Affiliate Network. He is a US Air Force Officer and A-10C Weapons Instructor Pilot with combat tours in Afghanistan and Libya.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia also has experience working with human rights-based NGOs and

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia also has experience working with human rights-based NGOs and